The past few months have been bleak. Not only has a dark shadow been cast over U.S. policing but now we have been alerted of yet another horrible truth: The CIA has been torturing people who are suspected to have ties to terrorist organizations. “Alerted” is perhaps the wrong word as it denotes something new coming to the fore. Grotesque as it is, here in the U.S., we’ve known since before President Obama that when it comes to “Muslim jihadists,” the U.S. will take any measure to ensure the Homeland Security Advisory chart does not surpass blue.

Some might say that Jordan Davis, Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride et al. and those tortured by the CIA have little in common. I wouldn’t have been able to connect the dots if not for the public thinking of individuals such as Ta-Nehisi Coates and J. Kameron Carter (I consider Carter to be the “Michael Jordan” of theology right now). However, I want to suggest that Eric Garner and the nameless tortured are byproducts of a “normalizing gaze” that attempts to differentiate non-citizens from citizens.

Ultimately, the only way to overcome this bipolarity is by looking to the resurrected body of Jesus Christ for what it means to be truly human.

Citizens vs. Non-Citizens

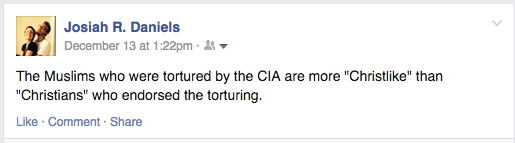

Awhile back, I made this comment on Facebook:

I received some interesting feedback. The discussion successfully avoided the pitfall of turning into a cyber-boxing-match and was instead a dialogical spar.

The statement is controversial on its face but what I was attempting to get at runs deeper than sexy statements.

Let me just admit that the prism from which I interpret all of reality is highly influenced by the Orthodox Christian faith. Therefore, I take for granted the sanctity of all human life based solely on the grounds that YHWH created us in his image; God created us, male and female. In God’s image we were created. Female and male God created us (Gen. 1:27).

In J. Kameron Carter’s gargantuan book on Race, he insists that religion and the nation-state have been co-conspirators in creating ways to label certain persons “in” and other persons “out.” Thus, the black souls who arrived in Virginia in 1619 were not only viewed as non-citizens, but they were also understood to be barbarians who needed to be disciplined in a “Christianity” that sought to subjugate their bodies. For Carter, this “pseudotheological” move is not unique to the corridors of the church. Pseudotheology permeates society as a whole as politicians, anthropologists, scientists and philosophers justify violence towards certain persons based on the “sovereignty” of the state in conjunction with the social construct of race.

Whether it be through a “normalizing gaze” or more overt measures like imprisonment or execution, the state seeks to transform “disobedient” persons to its concept of what is normal, right and beautiful. Throughout his book, Carter reveals the ways in which the church has disappointingly “ventriloquized” society’s definitions of what it means to be truly human. Those who are unable or unwilling to kowtow to society’s definition of the normal face the threat of exclusion or termination.

The Seduction of Pseudotheology

In my opinion, Christians who wish to argue the merits of torturing a few “crazy terrorists” as a viable option to “save lives” have been seduced by the pseudotheology that Carter criticizes.

Consequentialist thinking is not only problematic theologically, but it also proves to be incorrect based on what we know concerning the “success rate” of torture. It doesn’t matter that the data regarding torture deems it to be fruitless. I’d say Christians–Evangelicals and Mainliners alike–make an exception for torture not based on data, but based on poor interpretations of Romans 13 along with a general disdain for Muslims.

The slave master’s whip and the torture dungeons of the CIA tell us something about normalizing or disciplining “disobedient” bodies here in the states. Since its illegitimate beginnings, this nation has sought ways to control those whose culture, religion and bodies differ from their colonial counterparts. Even though Eric Garner had “rights under the law” these “rights” were unable to give him the oxygen he needed to sustain his life. This is why Ta-Nehisi Coates’ voice is necessary as he refuses to interpret the American project from an ahistorical perspective. Furthermore, Coates also sees the nexus between pseudotheology and the plundering of black and brown bodies.

According to this pseudotheology, the police officer who performed a drive-by shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice is actually performing his civic duty by eliminating those who are unable to “fit the mold” of a true American. Not only did police officer Darren Wilson valiantly rid America of yet another “thug,” but in Wilson’s own pseudotheological imagination, he acted as an exorcist when he shot Brown who resembled a “demon” rather than a human being. Whether it be baptism by waterboarding or a vigilante cloaking his heinous act in divine equivocation, pseudotheology remains to be an ideology employed by those in power.

The Resurrected Body (Conclusion)

Power, in the classical sense, was continuously rejected by Jesus. As Israel’s Savior-King, Jesus embraces the Jewish ideal of God’s reign which sets itself in opposition to the Roman Empire (Lk. 1:46-55). YHWH is King, Caesar is not (Lk. 20:25). The poor will inherit the Kingdom, the rich will fade away (Mt. 5:3; Lk. 6:24). Dissimilar to Gentile tyrants, God’s Kingdom is one where the last are first and the first are last (Mt. 20:25-28). Jesus also reminds everyone that the temple is not a rendezvous point for movers and shakers but is a sacred space for all tongues, tribes and nations (Mk. 11:15-19). With a litany like this, it only makes sense that Jesus got himself crucified.

Crucifixion was the way the powerful reminded the powerless that death would be the final word. To be among those crucified is to be remembered in the annals of history as someone who refused to be molded to the patterns of the empire. Jesus is not only tortured and executed because of a few controversial statements–or because of his “heretical” religious claims. No, Jesus is flogged and murdered because the body he occupies continuously presents itself as a threat to imperial power (Mt. 2; Jn. 18:28-38, 19:12-16).

Christ defeats death and all its friends through his bodily resurrection (Eph. 1:20-23; I Col. 2:15). This is where I stake my claim: Despite its best efforts, the empire is ultimately unable to discipline the true humanity of Jesus Christ. If the church at large represents the body of Christ, what might this mean for those who worship the God who says no to the disciplinary tactics of the state? God’s saying “no” to imperial hegemony can be seen in God’s saying “yes” to the humanity of Gentiles despite the fact that their bodies differ from the Abrahamic people (Gen. 17:9-14; cf. Acts 15; Gal. 2:11-21). In God’s Kingdom, to be recognized as a citizen or a human does not necessitate violent contortion. On the contrary, the ekklesia welcomes all who pledge allegiance to the Lamb regardless of their sex, class or race (Rom. 10:12; I Cor. 12:13; Gal. 3:28; Eph. 2:11-22; Col. 3:11). Thus, Brian Bantum’s classification of life in the Christian colony as “mulattic” correctly captures the biblical mandate for inclusivity.

It seems to me that those who wish to claim the title of Christian but deny the racial components of policing or justify the existence of Guantanamo Bay may actually be a kind of “pseudo-Christian.” In an ironic but chilling sense, those executed or tortured by State authorities are a better representation of Christ than the pseudo-Christians who take no issue with the social conditions that lead to the oppression of marginal people groups. To be a Christian, in the proper sense, requires a denunciation of state-sanctioned torture and execution; especially when this torturing and killing is exerted over/against marginal communities. It is evident, made plain by the resurrection, that within The Kingdom of God, a place that celebrates the new, true humanity, there is no room for violent subjugation of the “other” (Mt. 5:43-48; Lk. 6:27-36; Rom. 12).

Ultimately, I hope that we Christians would learn to align ourselves with the Apostles in declaring that “we believe in the resurrection, we believe in a life that never ends.”

Missio Alliance Comment Policy

The Missio Alliance Writing Collectives exist as a ministry of writing to resource theological practitioners for mission. From our Leading Voices to our regular Writing Team and those invited to publish with us as Community Voices, we are creating a space for thoughtful engagement of critical issues and questions facing the North American Church in God’s mission. This sort of thoughtful engagement is something that we seek to engender not only in our publishing, but in conversations that unfold as a result in the comment section of our articles.

Unfortunately, because of the relational distance introduced by online communication, “thoughtful engagement” and “comment sections” seldom go hand in hand. At the same time, censorship of comments by those who disagree with points made by authors, whose anger or limited perspective taints their words, or who simply feel the need to express their own opinion on a topic without any meaningful engagement with the article or comment in question can mask an important window into the true state of Christian discourse. As such, Missio Alliance sets forth the following suggestions for those who wish to engage in conversation around our writing:

1. Seek to understand the author’s intent.

If you disagree with something the an author said, consider framing your response as, “I hear you as saying _________. Am I understanding you correctly? If so, here’s why I disagree. _____________.

2. Seek to make your own voice heard.

We deeply desire and value the voice and perspective of our readers. However you may react to an article we publish or a fellow commenter, we encourage you to set forth that reaction is the most constructive way possible. Use your voice and perspective to move conversation forward rather than shut it down.

3. Share your story.

One of our favorite tenants is that “an enemy is someone whose story we haven’t heard.” Very often disagreements and rants are the result of people talking past rather than to one another. Everyone’s perspective is intimately bound up with their own stories – their contexts and experiences. We encourage you to couch your comments in whatever aspect of your own story might help others understand where you are coming from.

In view of those suggestions for shaping conversation on our site and in an effort to curate a hospitable space of open conversation, Missio Alliance may delete comments and/or ban users who show no regard for constructive engagement, especially those whose comments are easily construed as trolling, threatening, or abusive.