There have been some absolutely terrible moments during the past few weeks.

- A video of Ahmaud Arbery, a black man shot down by two white men as another filmed the killing. It took the release of the video to compel the authorities in Georgia to press charges.

- Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old black woman, shot to death by police officers in Kentucky when they entered her home with a no-knock warrant and were met by gunfire from her frightened boyfriend.

- Christian Cooper, a black man and avid birdwatcher in New York’s Central Park, asks a white woman to leash her dog per park regulations. In response, the woman dials 911. “I’m going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life,” she says.

- Another video, this one of George Floyd being killed by Minneapolis police this week. A knee pressed into the black man’s neck. We hear him gasp, “I can’t breathe. Please, I can’t breathe.”

Each of these instances of racial terror is but a glimpse at the potential horrors regularly faced by African Americans in a nation whose collective imagination remains deeply infected with white supremacy and anti-black racism. But the disdain for black life is not always so vivid; it often recedes into the background where, for those of us who are white, it can be ignored.

Troubling Dichotomies…

For example, last week a friend tagged me in her social media post. This African American woman observed that when driving through the north side of Chicago in predominately white neighborhoods, most of the people weren’t wearing masks. Here on the south side, she noted, most of the black residents are wearing masks. I’ve noticed the same thing. Why, she wondered, the difference?

Or what about the recent protests against the stay-at-home orders which have been, at least from photo and video evidence, made up mostly of white people? The rather dramatic images of gun- and flag-wielding protestors has provoked some uncomfortable questions on my side of the city: What would happen if a group of black men showed up at the state house so heavily armed? Why is it that the protests began after it was shown that COVID-19 is disproportionately killing people of color, especially African Americans and indigenous people? Why is it so hard for these white people to understand that six feet of distance and face masks aren’t about their personal liberty but about the survival of their vulnerable neighbors, often people of color?

Of course, there are plenty of white people who understand that social distancing is about loving vulnerable people. And there are some people of color who think the economy should have been reopened yesterday. But, at least from my vantage point, this troubling dynamic falls largely along predictable racial lines. Those with the protection of our privilege are quick to discount precautionary measures; some have even taken to protest. Others, who are left vulnerable by economic and health disparities, are carefully observing all measures that might protect their communities.

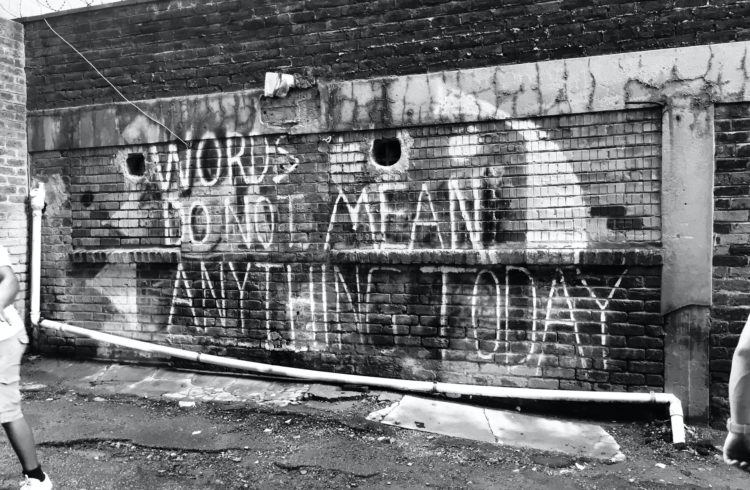

Truths that Are Being Revealed

It seems like a mirror is being held up to our country. This season of crisis is revealing who we are—who we really are. About a natural disaster that devastated his country, the El Salvadorian theologian Jon Sobrino wrote, “The earthquake is a catastrophe, but it is also a bearer of truth. It is an X-ray of the country in its many dimensions… it reveals the truth that people would rather keep hidden.”[1] It seems like a mirror is being held up to our country. This season of crisis is revealing who we are—who we really are. Click To Tweet

Will white Christians have eyes to see what is being revealed?

Our past performance doesn’t leave me hopeful. As Drew G. I. Hart writes, “The white church…has often been silent in response to the four hundred years of assault on black humanity. At times it has outright taken the lead in antiblack racism.”[2] This is an ugly reality to confess, but the truth behind it is even worse.

A crisis may reveal, but the realities it uncovers are actually not hidden all that well. Sobrino writes, “That reality is certainly ‘known’ by the people who suffer it, but it is not effectively ‘recognized’ by the powerful.” And this is why, if I’m honest, I struggle to hope. Because the terrible racial disparities, the instances of deadly racism, the underlying current of white supremacy which animates this country have all been long known by those who have suffered from them. Yet those of us whose power is wrapped within racial privilege have mostly refused to recognize reality.

The terrible truth is that white Christians have found more in common with other white people than we have with Christians of color. The terrible truth is that white Christians have found more in common with other white people than we have with Christians of color. Click To Tweet

Race, not the Christian faith shared with the African American sisters and brothers who suffer this country’s racism, is what most shapes our priorities and perspectives. This is what is once again being revealed.

A Glimmer of Hope

In her important book Be the Bridge, Latasha Morrison writes that the “church will not be a leading example in racial healing until we feel the weight of communal guilt and shame and then allow it to push us into the truth.”[3] And as strange as this might sound, it’s the possibility of communal guilt and shame within our white churches that leaves me with a little bit of hope. While we cannot remain in shame forever, both the pandemic and the responses to recent tragedies have revealed how much we have to be ashamed of. We are guilty of abandoning black brothers and sisters to this country’s insatiable racist appetites.

Might we be willing to open our eyes to the truth? If so, then there is yet hope for white Christians. Our God remains powerful enough to draw us into true solidarity with spiritual family members who share our faith but not our race. The only question is whether we or not we will resist his call. So far, the evidence is not encouraging.

(Editor’s note: for a deeper dive into this topic, we recommend that you check out David’s new book, Rediscipling the White Church: From Cheap Diversity to True Solidarity, an InterVarsity Press/Missio Alliance partnership title.)

[1] Jon Sobrino, Where is God? Earthquake, Terrorism, Barbarity, and Hope (New York: Orbis, 2004), 16.

[2] Drew G. I. Hart, Trouble I’ve Seen: Changing the Way the Church Views Racism (Harrisonburg, Virginia: Herald Press, 2016), 120.

[3] Latasha Morrison, Be the Bridge: Pursuing God’s Heart for Racial Reconciliation (Waterbrook Press, 2019), 78.

Missio Alliance Comment Policy

The Missio Alliance Writing Collectives exist as a ministry of writing to resource theological practitioners for mission. From our Leading Voices to our regular Writing Team and those invited to publish with us as Community Voices, we are creating a space for thoughtful engagement of critical issues and questions facing the North American Church in God’s mission. This sort of thoughtful engagement is something that we seek to engender not only in our publishing, but in conversations that unfold as a result in the comment section of our articles.

Unfortunately, because of the relational distance introduced by online communication, “thoughtful engagement” and “comment sections” seldom go hand in hand. At the same time, censorship of comments by those who disagree with points made by authors, whose anger or limited perspective taints their words, or who simply feel the need to express their own opinion on a topic without any meaningful engagement with the article or comment in question can mask an important window into the true state of Christian discourse. As such, Missio Alliance sets forth the following suggestions for those who wish to engage in conversation around our writing:

1. Seek to understand the author’s intent.

If you disagree with something the an author said, consider framing your response as, “I hear you as saying _________. Am I understanding you correctly? If so, here’s why I disagree. _____________.

2. Seek to make your own voice heard.

We deeply desire and value the voice and perspective of our readers. However you may react to an article we publish or a fellow commenter, we encourage you to set forth that reaction is the most constructive way possible. Use your voice and perspective to move conversation forward rather than shut it down.

3. Share your story.

One of our favorite tenants is that “an enemy is someone whose story we haven’t heard.” Very often disagreements and rants are the result of people talking past rather than to one another. Everyone’s perspective is intimately bound up with their own stories – their contexts and experiences. We encourage you to couch your comments in whatever aspect of your own story might help others understand where you are coming from.

In view of those suggestions for shaping conversation on our site and in an effort to curate a hospitable space of open conversation, Missio Alliance may delete comments and/or ban users who show no regard for constructive engagement, especially those whose comments are easily construed as trolling, threatening, or abusive.